ANWYN'S COUNTERPOINT:

Dr. Brad Birzer and Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth

"[Myths are] lies and therefore worthless, even though breathed through silver," [said Lewis.]

"No," said Tolkien. "They are not lies."

--As recorded by Humphrey Carpenter in The Inklings

Since the very publication of The Lord of the Rings, theories have abounded on the deeper significance or meaning that Tolkien intended his story to have. The atomic bomb, WWII at large, psychoanalytic journeys through adolescence, Frodo as Christ, Gandalf as Christ, Aragorn as Christ, etc. rampage ad nauseam, and the argument of Tolkien himself that he "despised allegory" becomes tired and cannot carry the fight alone. A shift in perspective is warranted, one that has a basis in other Professorial remarks: that The Lord of the Rings is decidedly a work saturated with, though not intoxicated by, Christianity; that though no one figure in the story is meant to represent or can be interpreted to resemble Christ, still the most prominent characters embody severally the highest virtues known to moral man; that death itself is a Christian reward for godly persons and heroic deeds; that modernism can be successfully shunned by one living in the modern world; that humans reach their highest potential when fulfilling God’s purpose; and that all myths contain fragments of a larger, objective truth. Since the very publication of The Lord of the Rings, theories have abounded on the deeper significance or meaning that Tolkien intended his story to have. The atomic bomb, WWII at large, psychoanalytic journeys through adolescence, Frodo as Christ, Gandalf as Christ, Aragorn as Christ, etc. rampage ad nauseam, and the argument of Tolkien himself that he "despised allegory" becomes tired and cannot carry the fight alone. A shift in perspective is warranted, one that has a basis in other Professorial remarks: that The Lord of the Rings is decidedly a work saturated with, though not intoxicated by, Christianity; that though no one figure in the story is meant to represent or can be interpreted to resemble Christ, still the most prominent characters embody severally the highest virtues known to moral man; that death itself is a Christian reward for godly persons and heroic deeds; that modernism can be successfully shunned by one living in the modern world; that humans reach their highest potential when fulfilling God’s purpose; and that all myths contain fragments of a larger, objective truth.

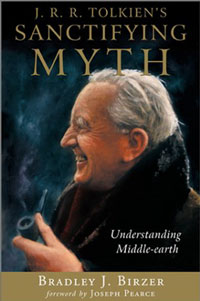

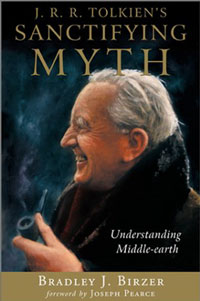

Dr. Brad Birzer’s new book, Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth, contains all these points and many more, richly supported by primary sources and the observations of those surrounding J. R. R. Tolkien during his life. As a Catholic, like Professor Tolkien, Dr. Birzer is deeply sympathetic to Tolkien’s struggles with modernism, both in the world around him and inside the organized church. Birzer gently lays out the different facets of Tolkien’s belief system and clearly shows how each affected the writing of The Lord of the Rings and its appended works. For those of us who have long tried to reconcile the Christianity of The Lord of the Rings with Tolkien’s clear desire that the work not be looked upon as a fable or a representation, Birzer’s book is the fresh air we have been looking for–everything "set out fair and square with no contradictions" but with sound reasoning supporting the thesis that Tolkien’s paramount desire was to use myth to inform the greater truth.

I had the pleasure of a recent conversation with Dr. Birzer, in which he shared some of the motivations and circumstances that brought about his writing. A history professor at Hillsdale College in Michigan, Dr. Birzer observed that his position in a small liberal arts school gives him a considerable amount of freedom in his academic life. Because his administration puts the emphasis on teaching rather than on publishing, he is able to pursue projects that, like Sanctifying Myth, are more literary in nature than historical, but it is obvious that his historical studies prepared him for the painstaking research required by Myth. "If I were at a state school I’d have to publish in history," he explains. "My approach to Tolkien is ‘liberal artish’–not social science-based." He says that he attempted to come at Tolkien as objectively as possible–not an easy feat after having been a Tolkien reader for 25 years. When asked to elaborate upon the liberal arts perspective, he offers, "The liberal arts approach–I really tried to ask a couple of basic questions: What is the human person? What is the relationship of the person to God, to society–those are the fundamental questions of liberal arts, so that’s how I approached it."

His method has resulted in some keen observations about Tolkien as well as a seamless drawing together of many views already published elsewhere, largely by other Christian scholars. "I tried really hard to ask questions without expecting a certain answer," he observes. "Now having said that, I really tried to put my mind into the mindset of what an English Roman Catholic would have thought, between two world wars. There are so few English Roman Catholics, and he would have been aware of all of them. I looked for who was writing what in the ’20s, ’30s, and found a number of parallels [between published works and Tolkien’s thinking]." In particular, Birzer cites the works of Christopher Dawson, a friend of Tolkien’s friend Havard whom Tolkien met on a few occasions. Birzer makes it clear that though Dawson was something of a recluse and did not really attend meetings of Tolkien’s friends in the form of the Inklings, Tolkien was very aware of Dawson’s philosophic Catholicism.

The largest gem mined out of the wealth of information Birzer drew upon is identified in the title of his book. He expounds upon Tolkien’s desire to sanctify myth and through myth, reality. Birzer describes once again, in case any of us have missed it over the years, the flaming acrimony leveled at Tolkien by rabid modernists, to whom anything not dealing with "those fundamental human concerns through which societies ultimately define themselves–religion, philosophy, politics, and the conduct of sexual relationships" is simply trash. Those words were taken from a review by one Andrew Rissik, writing for the London Guardian and quoted by Dr. Birzer. But what Birzer brings to the forefront is Tolkien’s belief that societies shouldn’t define themselves by those things, and that indeed, the sanctification Tolkien so earnestly desired begins with putting those elements in their proper places and dealing instead with the virtues so eloquently described by Tolkien in the pages of Lord of the Rings–heroism, sacrifice, treatment of one’s friends, treatment of one’s enemies, and understanding of the higher purpose to which one is called. I’m quite sure that Tolkien would squirm in his chair or spin in his grave at talk of societies defining themselves by their sexual relationships, though unfortunately it is a fact of modern life. He was called to a higher standard and tried throughout his lifetime to sound that call to others.

Life under the anti-modernist Catholic umbrella is not all harmony and sunshine, however. Dr. Birzer does not mask the natural friction between Tolkien’s ardent Catholicism and the Protestantism of one of his closest friends, C. S. Lewis. While he reiterates what has been pointed out by others, that Lewis was personally biased against Catholicism while maintaining a broader view in his outside writings, he also makes clear the less well known idea that Tolkien had his share of prejudices against Protestantism. Birzer gives us the startling viewpoint that Tolkien blamed Protestants for causing the Enlightenment and thus modernism, by rejecting the authority of the Pope during the Reformation. Appended to this idea is the notion that a lack of uniform Christianity results in a much higher sense of nationalism, and thus, potential for national conflict. In defense of this perspective, Dr. Birzer, in our conversation, painted for me a picture of the medieval world that Tolkien so embraced. "[Tolkien’s] understanding of Catholicism and the Middle Ages–you have Latin that all the scholars speak, you have a certain literature, the Bible, papal encyclicals and council papers, then national cultures–ethnic cultures. English (of Chaucer), French, Hungarians, etc. But in terms of larger overview, they are tied together. A scholar leaving Hungary could go to Oxford and speak Latin." So the umbrella of Catholicism and scholarly Latin was more important than the existing nationalism, even though ethnic differences continued to be upheld. Dr. Birzer referred to "Christiana res publica. Politically decentralized but culturally unified–higher culture, not lower folk culture."

It is clear that Tolkien longed for this kind of disparate national entity–Aragorn’s hands-off approach to the Shire once he became king makes that point beyond doubt–but that he still wished for that protective umbrella of Catholicism and Latin for all. Our modern "multicultural" craze tends to bear out the peacemaking possibilities of Tolkien’s wish–with the lack of submission to a higher authority comes a search for a guiding principle, and when people make nationalism and heritage their ultimate calling, we see firsthand today the results. Nation against nation, citizen of one continental descent against citizen of another. It was this kind of conflict Tolkien was anxious to alleviate with his sanctifying force.

Dr. Birzer makes a terrific case for what he sees as Tolkien’s ultimate objective: the sanctification of the whole world and his small part in it through subcreation of truthful myth. But does Dr. Birzer, or did Tolkien, see any hope of achievement of these lofty goals? I reminded him of the fate of Christians who speak up publicly and the common rallying cry of the modernist: You can’t push your morality on others. He answered at length.

"Let me put it this way–I think this is how Tolkien would have answered that. Essentially, people who are doing things in politics, that’s great. But every aspect of society needs to be sanctified. It doesn’t matter if it’s a book, or a video game, or a family. It doesn’t demand moral rigor in the sense of pushing morality on others. Tolkien would be distraught at that; that’s the tool of the enemy. Tolkien was open and wanting to come at people on their own terms. But I also think nothing is going to change politically for any long period of time before culture has been changed. Culture is the beginning of all things. Not until the culture has been changed will anything else be changed–economics, politics, etc. Tolkien showed this through Sam: Always use your gifts for the greater good. Of course we’re fallen, but use your gifts and follow the cardinal virtues–prudence, temperance, justice, fortitude, faith, hope and charity. Of course, we don’t do that–it’s God working through us. Frodo and Sam have to leave their community to save it, and go into hell with the Ring, but they do it.

"The mystery is how we do what we’re supposed to do, regardless of the outcome or why. You never know how anything you do–anything you do–will affect anything, even a thousand years from now, even someone who just happens to see you, what they will pass on to their children. Tolkien said each one of us is an allegory of God, an allegory of Christ. We have eternal life; we’re given this gift of pilgrimage here. Tolkien was very clear: We do our part and let God take care of the rest. We can’t change the world. That’s what Sauron and Melkor tried to do; they wanted to see what they could do, and of course it’s not about them.

"I was born in September of 1967. Why then? Why not a hundred years ago? Why not a hundred years from now? Each one of us has a purpose. [The apostle] Paul talks about this. We are altogether small beings that form the body of Christ. And to me that’s what the Fellowship is about. A small group of small people, with disparate gifts–and it failed sometimes! Sometimes it failed miserably! Boromir failed, and was redeemed by his sacrifice."

Dr. Birzer is clear that Tolkien’s characters were ultimately all about the love required to attain higher purpose. And like our dear Quickbeam, he knows the secret truth about Samwise Gamgee–"He is the hero of the story," Birzer says.

"If we can’t be loving, we can’t be anything. Every one in the Fellowship was loving. Gandalf willing to sacrifice himself–an act of love. Frodo, same thing. Sam, same thing. Aragorn confronting Sauron was loving. I think we do our duty, see what happens, and not be too impatient.

"It may take a thousand years before the culture’s redeemed. If we push it, we only cause problems. We can only lead by example. That’s how the early church was formed. They didn’t push it. They died in the arenas over and over again."

But does he see any realistic hope for the sanctification of civilization? Or, hearkening back to a time when a large majority of the western population was Catholic, re-sanctification? What about the inevitable fall of society?

"Tolkien did address this. He, like all of us, on some days was optimistic and some days pessimistic. There’s no doubt that we’re getting closer and closer together and we’re being homogenized. It’s good and bad. It’s bad in that we often take the lowest common denominator in order to agree with each other."

And apparently good in that a story like Tolkien’s can be easily passed around the entire world and free discussion can take place in every corner of the globe about whether Balrogs have wings and how Tolkien’s Christianity affects the character of, say, Boromir. Ultimately, if humans are getting closer and closer together, then their myths are more widely known to one another–and if each myth holds a fragment of truth, eventually society may put it all together. After all, Tolkien knew, as most twentieth-century writers apparently do not, that "the fantastic may tell us more about reality than scientific fact." Dr. Birzer definitely thinks so. He reminded me that fact and reality are not necessarily the same thing.

"[We have] blinders over our eyes so that we only see things in a certain age. Never in the Middle Ages would anybody blink an eye if somebody said they saw somebody come down with a halo. We limit ourselves by only trying to figure out what we can see, smell, touch. There’s a deeper reality. To Tolkien, myth was truth."

*****************

Dr. Brad Birzer’s book, Tolkien’s Sanctifying Myth, will hit bookstore shelves soon and can be preordered at Amazon.com. Enjoy!

--Anwyn

|

![[ Green Books ]](http://img-greenbooks.theonering.net/images/gb_logo.gif)

![[ Green Books - Exploring the Words and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien ]](http://img-greenbooks.theonering.net/images/gb_topnav.gif)