SPECIAL GUEST:

JRR Tolkien and World War I - Nancy Marie Ott

One has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel fully its oppression; but as the years go by it seems now often forgotten that to be caught in youth by 1914 was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years. By 1918, all but one of my close friends were dead.

— J.R.R. Tolkien, forward to The Lord of the Rings

This essay takes a speculative look at how J.R.R. Tolkien’s service in the British Army during World War I may have influenced his fiction, particularly The Lord of the Rings. I first read The Lord of the Rings as a seventh grader; at the time, I didn’t look beyond the surface of the story. What struck me while re-reading the book as an adult was how much parts of it sounded like accounts of World War I. While The Lord of the Rings is clearly not an allegory of World War I, there are a number of similarities between it and the war that hint at a connection between them.

It is dangerous to assume that an author’s life experiences are directly reflected in his or her fiction. Tolkien is not a World War I writer in the sense that, say, Siegfried Sassoon, Robert Graves, or Ernest Hemingway are. These writers directly portrayed their war experience in their stories and poetry. Instead, Tolkien’s war experiences are sublimated in his fiction. They surface in the sense of loss that suffuses the story, in the ghastly landscapes of places like Mordor, in the sense of gathering darkness, and in the fates of his Hobbit protagonists.

Tolkien himself stated that the war had only a limited influence on his writing. However, it is also true that people are shaped by times in which they live. I think it is likely that Tolkien drew on his memories of fighting on the Western Front while writing The Lord of the Rings – perhaps because at the time he was writing it, England was again engaged in total war with Germany, a war that in many ways was the continuation of the one in which he had served. Even though Tolkien denied that his writing was based on his life, he once wrote to his son Christopher regarding his war experiences:

… I took to 'escapism': or really transforming experience into another form and symbol with Morgoth and Orcs and the Eldalie (representing beauty and grace of life and artefact) and so on; and it has stood me in good stead in many hard years since and I still draw on the conceptions then hammered out.

Letter 73, Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien

World War I represented everything Tolkien hated: the destruction of nature, the deadly application of technology, the abuse and corruption of authority, and the triumph of industrialization. It interrupted his career, separated him from his wife, and damaged his health. Yet at the same time it gave him an appreciation for the virtues of ordinary people, for friendships, and for what beauty he could find amidst ugliness.

Tolkien’s Service in the Great War

J.R.R. Tolkien was at Oxford working on his degree in English Language and Literature when England declared war on Germany in 1914. Unwilling to leave Oxford, he joined the Officer's Training Corps, which deferred his enlistment until after he had finished his degree. His three closest friends, fellow members of a schoolboy club they called the TCBS (Tea Club and Barrovian Society, named for their fondness for meeting for tea at Barrow’s stores) also enlisted. Encouraged by his TCBS friends, Tolkien began to express himself through poetry, taking his first steps towards finding his voice as a writer.

After taking First Class Honors at Oxford in 1915, Tolkien enlisted in the New Army, the volunteer army that succeeded Britain's small professional army, which had been decimated early in the war. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the 13th Lancashire Fusiliers and eventually was appointed battalion signaling officer. Tolkien decided to marry his long-time love, Edith Bratt, in March, 1916. The terrible casualty rate among the British forces made it clear that he might never return from France.

J.R.R. Tolkien in uniform, 1916. (http://www.tolkien.com.br/valinor/jrrtolkien/fotos.asp)

Tolkien's battalion was sent to France in June 1916. He had three weeks of training at the British camp at Étaples, during which he was transferred to the 11th Lancashire Fusiliers. As battalion signaling officer, Tolkien was responsible for maintaining communication between officers in the field and the Army staff responsible for directing the battle. This information would be used to direct artillery fire to where it was needed, send or withdraw reinforcements, and support any gains the attackers made against the German lines. He would have learned how to make use of field telephones, flares, signal lamps, Morse code buzzers, carrier pigeons, runners, and other devices deemed necessary to keep the lines of communication open. Finally, when preparations were complete, his battalion was sent to the Front to join the great joint British-French attack that was supposed to break through the German lines: the attack that later was known as the Battle of the Somme.

Fortunately for Tolkien, his battalion was assigned to the reserves at the beginning of the battle. It did not take part in the initial British attack on the dug-in German positions on the Somme, which failed to achieve its predicted breakthrough and led to massive loss of life. (Of the 100,000 British soldiers who entered No-man's land on the first morning of the Battle of the Somme, 20,000 were killed outright; another 40,000 were wounded.) His battalion was ordered into the trenches about a week later. Day after day of tours in the trenches and rest periods interspersed with attacks followed. The Battle of the Somme continued for months as the British unsuccessfully attempted to break through the German lines, although they did manage to push them back. French forces fared somewhat better, but they too did not achieve the dramatic breakthrough that the generals had initially envisioned.

Tolkien took part in two major offensives against the Germans. On his first day in the trenches, his battalion was part of an unsuccesful attack on Orvillers, a village held by the Germans. The barbed wire had not been cut and many men in his battalion were killed by machine gun fire. His battalion also took part in the attack on the Schwaben Redoubt (a strongly fortified German position) at the end of September, 1916.

Battlefield conditions made his job as battalion signal officer extremely difficult. Conditions were far more chaotic than anyone had expected, with tangled wires, damaged equipment, and mud everywhere. Signalers could not use field telephones for important messages, as the Germans had managed to tap into the British telephone network. Even Morse code buzzers were forbidden, forcing signalers to use runners and sometimes even carrier pigeons.

Tolkien's time in the army was not completely wasted in terms of his creative life. As he later wrote to his son Christopher, some of the earliest development of his mythology and languages was done in canteens, at lectures, in crowded and noisy huts, by candle-light in tents, and even in dugouts under shell-fire. He admitted that it did not make him a good officer.

Despite the action he had seen, Tolkien was not wounded. His friends from the TCBS were not so fortunate. One was killed on July 1; another was killed in December. The deaths of his friends affected him greatly, paradoxically inspiring him to continue with his own work so that the legacy of their friendship would not be lost.

In late October, Tolkien contracted trench fever (a disease carried by lice) and was sent home to recuperate. He spent the rest of 1916 and early 1917 in hospital until his fever finally subsided. He was then posted to camps in England until the end of the war. Tolkien was reunited with his wife Edith and their first child was born during this period. He also began composing some of the tales that would later become the Silmarillion – in particular, the story of the sack of Gondolin and the story of Luthien and Beren (inspired by watching Edith dance and sing while they were walking in a hemlock wood).

Part II: The Great War and The Lord of the Rings

Landscapes of nightmare

The most noticeable way in which Tolkien’s wartime experiences are expressed in The Lord of the Rings is in his descriptions of the landscapes of evil. Key elements of the landscapes of Mordor, the desolation of Mordor, and the Dead Marshes are directly inspired from the landscapes of the trenches and No-man’s land of World War I. Tolkien clearly drew on his memories of the Western Front when describing the lands ruined by Sauron. As he later stated in one of his letters, "The Dead marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme."

Conditions in the trenches on the Somme were ghastly. To get to the battlefront, soldiers had to march through the night from their billets to the area immediately behind the lines, then pass through the network of support trenches and communication trenches until they arrived at the front lines. The frontline trenches were muddy and uncomfortable. To protect themselves as much as possible from German fire between attacks, the men stayed down in their trenches and dugouts. From the bottom of the trench, they could only see the sky above the earth and sandbagged walls. Fire steps on the side of the trench provided lookout perches and platforms for shooting at the enemy.

Foot traffic on a sunken road outside La Boiselle, 1916 (World War I: Trenches on the Web, http://www.worldwar1.com/foto/fww1512a.jpg)

No-man’s land – the area between the German and Allied front line trenches – was a torn-up morass of destroyed buildings, gray mud, and rubble from the chalky rock of the Somme area, pocked with shell craters and strung with defensive barbed wire. Corpses were everywhere, their faces turned black by exposure to the sun and rain. Rats fed on the unburied dead. Nothing grew in No-man’s land. The few trees that remained were little more than husks, stripped of their branches and leaves by gunfire. The land itself was shattered.

The devastation of Delville Wood, September, 1916. (World War I: Trenches on the Web, http://www.worldwar1.com/foto/gb109.jpg)

An attack meant "going over the top" of the trench and crossing No-man’s land to reach the German positions. Barbed wire defenses made it difficult to approach the enemy trenches and German gunners would shoot the British as they bunched up to pass through gaps in the wire. Soldiers took whatever cover was available in shell craters, sunken roads, and ditches.

1st Lancashire Fusiliers prepare to go "over the top," July 1, 1916 (World War I: Trenches on the Web,http://www.worldwar1.com/foto/gb105.jpg)

The parallels between the landscapes of No-Man’s Land and Tolkien’s landscapes of nightmare are striking. Mordor is a dry, gasping land pocked by pits that are very much like shell craters. Sam Gamgee and Frodo Baggins even hide in one of these pits when escaping from an Orc band, much as a soldier might have hidden in a shell hole while trying to evade an enemy patrol. Like No-Man’s Land, Mordor is empty of all life except the soldiers of the Enemy. Almost nothing grows there or lives there. The natural world has been almost annihilated by Sauron’s power, much as modern weaponry almost annihilated the natural world on the Western Front.

The desolation before the gates of Mordor is another savage landscape inspired by the Western Front. It is full of pits and heaps of torn earth and ash, some with an oily sump at the bottom. It is the product of centuries of destructive activity by Sauron’s slaves, a destruction that Tolkien stated would endure long after Sauron was vanquished.

Dreadful as the Dead Marshes had been, and the arid moors of the Noman-lands, more loathsome by far was the country that the crawling day now slowly unveiled to his shrinking eyes. … Here nothing lived, not even the leprous growths that feed on rottenness. The gasping pools were choked with ash and crawling muds, sickly white and grey, as if the mountains had vomited the filth of their entrails on the lands about.

- The Two Towers, Book IV, Chapter 2: "The Passage of the Marshes"

The sickly white and grey mud mentioned in this passage is very like the terrain of No-Man’s Land on the Somme, where the underlying chalk bedrock was churned up by artillery bombardment and turned the ground grey and white.

Results of an artillery bombardment on the Somme, July 1916. (World War I: Trenches on the Web, http://www.worldwar1.com/foto/mhq074.jpg)

Even today, the old trench lines of the Somme can be seen from the air as bands of white among the green fields. The whitest areas mark where the fiercest fighting occurred in 1916.

The horror of these landscapes is that they are not naturally produced but are a product of man’s destructive misuse of technology. Battlefields like this simply did not exist before World War I. In earlier wars, armies arrived on the battlefield, fought, and left. However the development of new, more destructive weapons (in particular, artillery) and the static nature of the war changed this. The battlefields of World War I experienced constant shelling and digging. It is not surprising that Tolkien's imagination should seize on these images of destruction as the embodiment of power and evil. These landscapes are similarly unnatural: a product of Sauron's destructiveness and his misuse of his power.

Frodo and Sam are aghast at this destruction of the natural world and feel physically sick as they journey through this blasted landscape. It all seems like a hideous dream. Later in the story, some of the soldiers of Gondor cannot bear even to pass though this area. They too feel that the desolation of Mordor is a hideous dream; many show signs of what sounds suspiciously like shell shock.

On the fourth day from the cross-roads, they came at last to the end of the living lands and began to pass into the desolation that lay before the gates of the Pass of Cirith Gorgor; and they could descry the marshes and the desert that stretched north and west to the Emyn Muil. So desolate were these places and so deep the horror that lay upon them that some of the host were unmanned, and could neither walk nor ride further north.

Aragorn looked at them, and there was pity in his eyes, for these were young man from Rohan, from Westfold far away, or husbandmen from Lossarnach, and to them Mordor had been from childhood a name of evil and yet unreal, a legend that had no part in their simple life; and now they walked like men in a hideous dream made true and they understood not this war nor why fate should lead them to such a pass.

"The Black Gate Opens", The Return of the King

In contrast to how shell shocked men were often treated in World War I, Aragorn has compassion for his stricken troops. He does not force them to cross the desolation of Mordor, but instead sets them to an alternative task of recapturing the island of Cair Andros.

The landscape of the Dead Marshes is also inspired by the Western Front. As Frodo, Sam, and their guide Gollum cross the Marshes, they see the ghostly, rotting forms of the dead soldiers of a war that had swept across the region thousands of years before. As Frodo tells Sam and Gollum,

"They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water. I saw them: grim faces and evil, noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, with weeds in their silver hair. But all foul, all rotting, all dead."

- "The Passage of the Marshes", The Two Towers

The dead lying in pools of mud is a powerful image of trench warfare on the Western Front, and is something that Tolkien would have undoubtably seen during his wartime service. As the autumn rains fell, the battlefield of the Somme turned into a stinking mire seeded with the rotting corpses of men and animals. The dead men that Frodo and Sam see are not physically present – only their ghostly shapes have been preserved –but their forms inspire horror and pity.

The landscape of Ithilien is in some ways like the landscape of rural France in the area behind the front lines. Although there is evidence of the nearby conflic – a few damaged buildings, some shell craters, and the general debris of war – the landscape is otherwise natural and unspoiled. It has not fallen fully under the dominion of war. So too is Ithilien, the deserted province of Gondor that had recently fallen under the dominion of Sauron. Although Sauron's Orcs have been at work, Ithilien retains some of its natural beauty. Sam and Frodo's feelings rise when they reach Ithilien, much as the spirits of soldiers rose when they were relieved of their tours in the trenches and could return to the comforts of the rear areas.

Another similarity between Ithilien and the rear areas in France is their close proximity to areas of deadly danger – either to the front or to the frontiers of Mordor. Behind the lines, the sounds of the bombardment were never far off. On the horizon the flashes of gunfire and the smoke and dust thrown up by the explosions might appear like a mountainous wall – similar to how Sam and Frodo see Mount Doom erupting in the lands beyond the Mountains of Shadow.

Sam and Frodo in Mordor, or a soldier on the Western Front?

Many of the ordeals that Sam and Frodo endure echo the physical torments that soldiers faced during World War I. It’s possible that they too were inspired by Tolkien’s wartime experiences.

The great thirst and hunger that Frodo and Sam often suffer during their journey into Mordor are reminiscent of the sufferings of soldiers in the trenches when food and water supplies could not get through. Soldiers did not typically carry much food or water with them. Supplies of food and water could be interrupted by shelling and often could not be brought out to men in forward positions like observation posts out in No-man’s land. Thirst was especially a torment in the summer, as there was often no drinkable water on the battlefield.

The clouds of ash and fumes that leave Frodo and Sam gasping for air on their journey through Mordor are also reminiscent of the use of poison gas in trench warfare. British gas masks were effective but uncomfortable and difficult to fight in. Gas often lingered in low spots like trenches and shell holes, precisely where men would go to shelter from machine gun fire and bombardments. While most kinds of poison gas were intended to kill or injure, some types of gas were intended merely to make the enemy miserable.

Tolkien often describes places where the Shadow has been at work (such as the Dead Marshes) as having a foul or bitter smell. Frodo, Sam, Gollum, and other characters are forced to endure the stink of these places. This is another echo of the battlefields of World War I, which stank of chemicals and death. The horrible smell was a torment to the soldiers fighting in the trenches. Draft animals (such as horses and mules) that were killed by enemy fire were usually left to rot because there simply was not enough time to dispose of them. The bodies of men who were killed in battle often could not be retrieved and buried, especially those who had died near enemy lines. Many men were literally blown to pieces by artillery fire, their bodies virtually unrecoverable. The stinking mud of the Dead Marshes also echoes the battlefields of Flanders, where men literally drowned in the mud.

Duckboard path in Flanders (Photos of the Great War, http://www.ukans.edu/~kansite/ww_one/photos/greatwar.htm)

The stars above Mordor and France

From their positions of comparative safety in the trenches, the soldiers could only observe the skies: sunrises, clouds, sunsets, the stars and moon at night, birds, and airplanes. At quiet times, bird song gave an eerie air of normality to the destroyed landscape of the front. This is another part of trench life that is echoed in The Lord of the Rings. While journeying towards Mount Doom with Frodo, Sam looks up from the barren No-Man’s land of Mordor and sees the beauty of the night sky above the devastation:

Far above the Ephel Duath in the West the night-sky was still dim and pale. There, peeping among the cloud-wrack above a dark tor high in the mountains, Sam saw a white star twinkle for a while. The beauty of it smote his heart, as he looked up out of the forsaken land, and courage returned to him. For like a shaft, clear and cold, the thought pierced him that in the end, the Shadow was only a small and passing thing; there was light and high beauty forever beyond its reach.

- "The Land of Shadow," The Return of the King

Sam's vision of beauty is very much like this account by an officer who served on the Somme and wrote under the pseudonym Mark VII:

The stars shine brilliantly and (these trenches facing north) I gaze at The Plough dipping towards High Wood. What joy it is to know that you in England and I out here at least can look upon the same beauty in the sky! … They have become seers – images of divine stability – guardians of a peace and order beyond the power of weak and petty madness. … They, at least, will outlast the war and still be beautiful.

- "Night in the trenches," A Subaltern on the Somme

Sam Gamgee, British Soldier

Tolkien had a great deal of respect for the privates and NCOs (non-commissioned officers) with whom he served in France. Officers did not make friends among the enlisted men, of course; the system did not allow it and there was a wide gulf of class differences between them. Officers generally came from the upper and middle classes; enlisted men usually came from the lower classes. However, each officer was assigned a batman – a servant who looked after his belongings and took care of him.

Tolkien got to know several of his batmen very well. These men and other men in Tolkien's battalion served as inspiration for the character Sam Gamgee. As Tolkien later wrote, "My 'Sam Gamgee' is indeed a reflection of the English soldier, of the privates and batmen I knew in the 1914 war, and recognized as so far superior to myself." Sam represents the courage, endurance and steadfastness of the British soldier, as well as his limited imagination and parochial viewpoint. Sam is stubbornly optimistic and refuses to give up, even when things seem hopeless. Indeed, the resiliency of Hobbits in general, their love of comfort, their sometimes hidden courage, and their conservative outlook owe much to Tolkien’s view of ordinary enlisted men. These traits enabled British soldiers not only to survive their tours of duty on the terrible battlefields of France, but to bravely attack and counter-attack the Germans.

The officer/batman paradigm also describes some aspects of Sam and Frodo's relationship. It is clearly not a formal one in a military sense, but it goes beyond that of an ordinary, civilian master and servant. Their relationship encompasses the closeness of soldiers who have been in combat together and who have depended on their comrades for their lives. Sam is steadfastly loyal to Frodo. He looks after Frodo's physical comfort – cooking, fetching water, and so forth – and helps Frodo on his quest as much as he possibly can, even carrying him up the slopes of Mount Doom when Frodo's strength gives out. He loves Frodo although he does not completely understand him. Sam also defends Frodo from danger when he is attacked by Shelob and rescues him from the Tower of Cirith Ungol. Sam and Frodo had been through terror and were tested against the lure of the Ring together, and were closer than a master-servant relationship would imply.

Orcs, Haradrim and Germans

It's often theorized that Orcs represent German soldiers. There certainly are similarities between them. Orcs are almost caricatures of the German enemy of trench warfare: the hordes of gray, pitiless warriors who overwhelm the brave and outnumbered defenders of the West. The Germans were aggressors in World War I; during their occupation of France and Belgium, they committed atrocities on the civilian population, burned libraries, and deliberately destroyed buildings of historical significance. The case for Orcs representing Germans gets stronger if their behavior in World War II is considered, where they committed acts of great evil including genocide.

Tolkien’s Orcs may have initially been inspired by his war experiences. The description of the sack of Gondolin in The Book of Lost Tales, Part II, written in 1917, has an eerie similarity to the type of industrialized warfare that Tolkien would have witnessed during the war. Morgoth’s dark and remorseless forces use great iron vehicles that seem much like tanks. Their sheer numbers and powerful, fiery weapons overwhelm the valiant Elvish warriors of Gondolin.

However, Tolkien himself dismissed claims that the Orcs represented a particular race or ethnic group, much less wartime Germans. "I've said somewhere else, even the goblins weren't evil to begin with. They were corrupted. I've never had those feelings about the Germans. I'm very anti that kind of thing." Tolkien admired the industriousness and spirit of the German people and railed against Adolph Hitler for perverting what he called the "noble Northern spirit" by associating it so closely with Nazism. He and Hitler’s propagandists had mined the same vein of Northern European mythology, with completely opposite results. Tolkien also often compared nasty and crude people who he encountered to Orcs. Clearly, Orcishness knows no national boundaries.

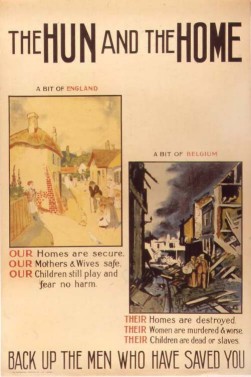

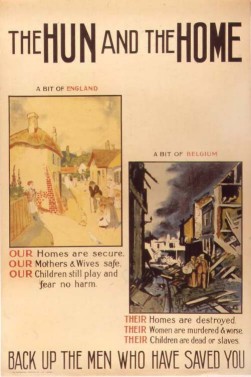

So what then are the Orcs? They may have been inspired by images of the rampaging Turkish, Mongol, and Persian armies that assailed Europe during the Middle Ages. They may also have been inspired by archetypal figures of evil and destruction: the Huns of Allied propaganda in both wars. Oddly enough, Kaiser Wilhelm II was the first to characterize German troops as 'Huns' during the European war with China in 1900, although he meant it as inspiration! This image of the pitiless Hun was later seized upon by Allied propagandists and used to demonize the Germans; a typical example is shown in the following British propaganda poster.

British propaganda poster (Take up the Sword of Justice: British Posters of World War I. http://gulib.lausun.georgetown.edu/dept/speccoll/britpost/britpost.htm)

The people in The Lord of the Rings who seem most similar to the Germans are not the Orcs, but the Haradrim. Like the Germans, the Haradrim are citizens of a powerful nation that is not inherently wicked but has been misled and corrupted by evil leaders. The Haradrim held old grudges against Gondor that were inflamed by Sauron to encourage them to go to war – again, similar to the situation in Germany during and between the two World Wars.

Unlike the Orcs, the essential humanity of the Haradrim is never in question. In one passage, Sam witnesses the death of a Haradrim soldier and in a flash of insight recognizes that his enemy is very much like he is:

He was glad that he could not see the dead face. He wondered what the man's name was and where he came from; and if he was really evil at heart, or what lies or threats had led him on the long march from his home; and if he would not really rather have stayed there in peace.

- "Of Herbs and Stewed Rabbit," The Two Towers

At the end of the War of the Ring, the Haradrim and other Southron and Easternling groups are shown mercy and are permitted to surrender – unlike the surviving Orcs, who are hunted down and killed. As king, Aragorn pardons the Easterlings and Southrons who gave themselves up and ends Gondor’s ancient conflict with Harad. This kind of peacemaking is what should have happened after World War I, but did not.

War Without End

The events in the War of the Ring have some parallels with World War I, although they are clearly different in scope and development. Tolkien may have been thinking of how it felt to be caught up in a terrible, seemingly unstoppable war when he was writing about the War of the Ring. The war against Sauron and the forces of darkness never ends. All victories are transitory, as Gandalf notes early in the story. "Always after a defeat and a respite, the Shadow takes another shape and grows again." Despite their valor, the forces of good cannot hope to gain victory by might of arms. All that the defenders of the West can hope for is to hold off their defeat for as long as possible.

Although the War of the Ring progresses in a very different manner than World War I did, the sense of their both being endless, unwinnable wars is much the same. Galadriel’s thought that she has been fighting a long defeat echoes the bleakest years of World War I, when despite the combined efforts of the Allies, the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary seemingly could not be defeated. In Middle-earth as in the real world, victory on the battlefield was transitory and often offered little gain for the lives lost.

The gathering darkness of the War of the Ring especially affects the people of Minas Tirith, who have borne the brunt of Sauron’s hatred. With Mordor only the width of the valley of the Anduin River away, they are well aware of their peril and grasp at even the slimmest tidings of hope. Pippin Took and Gandalf’s arrival in Minas Tirith set off a hopeful rumor that swept through the city. Pippin was supposedly the Prince of the Halflings who has come to offer allegiance to Denethor; every Rider of Rohan who comes to the aid of the beleaguered city was said to be bearing a Halfling warrior behind him. This rumor is very similar to a popular rumor in England during the early part of World War I. Russia supposedly had sent troops to England’s aid; the Russians were said to travel on unmarked trains and could be identified by the snow still clinging to their boots! Pippin regretfully had to destroy the hopeful rumor about the Halfling warriors; the rumor about the Russian troops in England died when they never materialized. Perhaps Tolkien included this incident to show that the population of Gondor suffered from the same wartime stresses as the population of England.

The Hobbits as returning veterans

The fates of Sam Gamgee, Frodo Baggins, Pippin Took and Merry Brandybuck after they return to the Shire are in many ways reflections of the fates that faced veterans returning after the war.

Merry and Pippin did not experience the terror and the sheer physical ordeal of bearing the One Ring to Mount Doom. Although they fought and were wounded in battle, they were not subjected to the constant and unending stress that Sam and Frodo were. It is as if they were members of an armed service that did not spend time in the trenches. After the war, they resume life as well-connected, upper-class Hobbits. Their experiences have matured them and trained them to take on leadership roles – as can be seen in their military planning to remove intruders from the Shire and in their direction (with Sam Gamgee) of restoration efforts after the Scouring of the Shire.

Sam and Frodo’s experiences during the war were much more hellish, resembling that of soldiers who had long tours of duty in the trenches. Of the two, Sam came through best. Like many veterans, he was able to put the terror of his wartime experiences behind him and successfully coped with the trauma of his journey to Mordor. His Hobbit resiliency and his focus on Frodo’s needs helped as well. Sam’s experiences broadened his parochial viewpoint and taught him wisdom. On his return to the Shire, he is hailed as a hero. Like Merry and Pippin, Sam takes on a leadership role in the restoration of the Shire. He marries his girlfriend, starts a family, and is elected mayor. Sam’s fate in some ways parallels Tolkien’s, who returned from the war, was reunited with his wife, started a family, and embarked on a successful academic and literary career.

On the other hand, Frodo could not put the War of the Ring behind him and had a difficult time coping with the trauma he suffered. In many ways, he is like the shell-shocked veteran of the trenches whose minds and spirits never recovered from the horrors they witnessed. The stress of his journey to Mordor was multiplied by the trauma he suffered from bearing the One Ring. Frodo had intrusive memories of being wounded by the Witch King’s knife, Shelob’s stinger, and Gollum’s teeth. He was often ill and eventually dropped out of the social life of the Shire. His spirit was broken by the evil effect of the Ring, to which he finally succumbed. Frodo cannot find peace or rest in the Shire, and must leave it to seek healing in the Blessed Realm.

The Passing of an Age

One final point of similarity between World War I and The Lord of the Rings is an emotional one: the sense of loss and sorrow at the passing of an age.

Most of Europe had known peace for over a generation before 1914. Europeans had made great strides in the sciences and the arts. Socialists preached the brotherhood of the working classes. Progress was considered to be proper and inevitable. Exciting new technologies would bring great benefit to people. World War I saw the destruction of this world. European society was wrenched into new patters as the war grew bloodier and the entire population became involved in the war effort. After the war, Europe never returned to what it was before. Science and technology had proved to be easily misused in the cause of war. Germany, Russia, and Austria-Hungary had fallen, their leaders unforgiven by the citizenry whose sons had been fed to the Moloch of the industrialized battlefield. Much that was beautiful in Europe lay in ruins. Millions of young men who would have contributed much to society were dead or maimed, their families and communities overwhelmed at dealing with this trauma. Noncombatants everywhere had suffered greatly. There was personal grief at the deaths of loved ones, and grief at the death of a way of life. In many ways, the new Modern age seemed a lesser one.

The Lord of the Rings is suffused with a similar sense of grief and sorrow. It too is about the end of an era. The age of the Elves is finished and the time of the dominion of Men is at hand. After the War of the Ring, the last of the Noldor or High Elves return across the sundering seas to the Blessed Land of Valinor. The passing of the High Elves represents the loss of the highest traits of humanity: artistry, craftsmanship, nobility, splendor. All outcomes of the war are fraught with sorrow. If the One Ring is found, Sauron wins and will cover Middle-earth in a new darkness. If the One Ring is destroyed, Sauron is vanquished but the Elves will suffer great loss. Though necessary to defeat evil, the destruction of the One Ring will cause the three Elven Rings to fail because their power is based on it. As Galadriel says to Frodo,

"Do you not see how your coming to us is as the footsteps of Doom? For if you fail, then we are laid bare to the Enemy. Yet if you succeed, then our power is diminished and Lothlorien will fade, and the tides of Time will sweep it away."

"The Mirror of Galadriel," The Fellowship of the Ring

After Sauron’s defeat, the Elves will fade and pass into the West, the Dwarves will eventually dwindle, and much knowledge and beauty will be lost. Aragorn as King of Gondor will be left holding the pieces in an attempt to preserve what he can of the era that has ended and pave the way for the coming dominance of Men in Middle-earth. There is grief at the passing of the Elves and grief at the end of a way of life that had existed for thousands of years. The new Fourth Age of Middle-earth will be a lesser one.

The fact that The Lord of the Rings does not really have a happy ending gives it realism. Tolkien certainly knew that not everyone who returned from the war would be able to resume the lives they had left in England. Moreover, he could not have forgotten that many of the men who went so eagerly to war never returned. Neither group would be able to enjoy what they had fought for. In one of the most moving passages of the book, Frodo speaks for all who have been destroyed by the war:

"… I have been too deeply hurt, Sam. I tried to save the Shire, and it has been saved, but not for me. It must often be so, Sam, when things are in danger: someone has to give them up, lose them so that others may keep them."

- "The Grey Havens," The Return of the King

Perhaps Tolkien was thinking of his dead TCBS friends when he wrote this, or of the men who were forever lost on the battlefields of France. Perhaps he was thinking of the men maimed in body and mind who could not savor the end of the war and the Allied victory over Germany. This is the true aftermath of war: not just celebration and relief, but terrible loss and sorrow.

Bibliography

Carpenter, Humphrey. J.R.R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1977.

Carpenter, Humphrey, J.R.R. Tolkien, Christopher Tolkien. The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1981.

Fussell, Paul. The Great War and Modern Memory. New York: Oxford University Press, 1975.

Gilbert, Martin. Atlas of World War I. New York: Oxford University Press, 1994.

Gilbert, Martin. The First World War: a complete history. New York: H. Holt, 1994.

Macdonald, Lyn. Somme. London: Michael Joseph, 1983.

Mark VII, pseudonym. A subaltern on the Somme in 1916. New York: E. P. Dutton & company. 1928.

McCarthy, Chris. The Somme: The day-by-day account. London: Greenwich Editions, Bibliophile House, 1996.

Norman, Phillip. "The Prevalence of Hobbits." First published in the New York Times Magazine. New York Times Company, 1967.

Photos of the Great War. http://www.ukans.edu/~kansite/ww_one/photos/greatwar.htm

Take up the Sword of Justice: British Posters of World War I. http://gulib.lausun.georgetown.edu/dept/speccoll/britpost/britpost.htm

Taylor, A. J. P. The First World War. New York: Perigee, 1963.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Fellowship of the Ring: being the first part of The Lord of the Rings. Boston : Houghton Mifflin Co., 1965, 1986.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Return of the King: being the third part of The Lord of the Rings. Boston : Houghton Mifflin Co., 1965, 1986.

Tolkien, J. R. R. The Two Towers: being the second part of The Lord of the Rings. Boston : Houghton Mifflin Co., 1965, 1986.

Winter, J. M. and Blaine Baggett. The Great War and the shaping of the 20th century. [Book] New York: Penguin Studio, 1996. [Videorecording] A KCET/BBC production in association with the Imperial War Museum; executive producer Blaine Baggett, 1996.

Winter, J.M, Geoffrey Parker, and Mary R. Habeck, eds. The Great War and the Twentieth Century. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000.

World War I: Trenches on the Web. http://www.worldwar1.com

Acknowledgements

My thanks go out to everyone who discussed the connections between J.R.R. Tolkien’s work and World War I with me. Your thoughts and input helped immensely when writing this essay.

|

![[ Green Books ]](http://img-greenbooks.theonering.net/images/gb_logo.gif)

![[ Green Books - Exploring the Words and Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien ]](http://img-greenbooks.theonering.net/images/gb_topnav.gif)